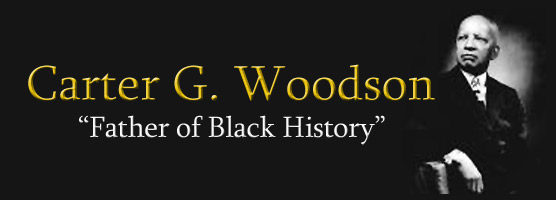

Black History Month’s roots extend back to 1915 when its founder, Carter G. Woodson (the author of the seminal work The Mis-Education of the Negro), created the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. Woodson, a Harvard graduate, created the association as a way of producing, accumulating, and canonizing scientific history about Black people. He hoped these findings would transform race relations by dispelling propagated myths concerning “scientific evidence” regarding the intellectual inferiority of Black people.

The following year, 1916, Woodson decided to compile the association’s scholastic efforts and publish its scientific data. This led him to create The Journal of Negro History. Eight years later, in 1924, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History created Negro History and Literature Week. Woodson chose to observe this week during the second week of February for reasons of tradition and reform. In Woodson’s estimation, the month of February encompassed the birthdays of two great Americans who played a prominent role in shaping Black History, namely Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, whose birthdays are the 12th and the 14th, respectively.

In 1926, this week was renamed Negro History Week because Woodson wanted to expand the week’s focus and interests. It took until 1976–fifty years after the creation of The Journal of Negro History—for us to begin celebrating Black History Month. In 1976, an association of young African Americans influenced by Woodson’s work and vision successfully advocated for the holiday to be expanded from a week to a month, and for the name to be changed from Negro History Week to Black History Month. Since its origin, it has sought to both create and celebrate knowledge about Black existence, in North America and beyond.

Black History Month began as a rebuttal and negation of scientific racism. Scientific racism evolved during the Enlightenment era.[1] Many scholars believe that its origins can be traced back to Paris, France, and particularly to the research of Authur de Gobineau.[2] While scientific racism may have originated in France, it quickly spread throughout most of Europe and eventually migrated overseas to the United States. In our nation, scientific racism was deployed to dehumanize African Americans, justify their exploitation, and create a racialized hierarchy.

At its core, scientific racism was a group of social scientists who began turning towards scientific quantification and statistics in an attempt to construct law-like assumptions about societal and human development. When this shift in scientific rationale occurred, racial issues received the greatest attention, and the findings from these “studies” were produced and published widely in medical journals across the country. In 1735 Carolus Linnaeus, who was a biological taxonomist, documented in his essay “Systema Naturae” that human beings should be classified by race, stating that there were four racial classifications: “white, black, red, and yellow.” Linnaeus concluded his theory of racial classification by ascribing traits to each racial group saying, “whites [have proven] to be innovative and of a keen mind, [while] blacks were lazy and careless.”[3] While this was one of the first studies to do so, the concept of each race encompassing and exhibiting different mental and moral traits became a central part of this new scientific discourse.

Some of the earliest evidence of the implementation of scientific racism in the United States comes from the writings of Benjamin Rush. Rush was an acclaimed medical doctor, he served as a surgeon general in the Revolutionary Army and as a professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Furthermore, Rush was one of the founding fathers and signers of the Declaration of Independence. Rush often spoke out on the question of racial morality, and he wrote an article in 1799 entitled Observations Intended to Favor a Supposition That the Black Color of the Negroes Is Derived from the Leprosy where he articulated his views on “black pathology” saying that “the big lip, flat nose, woolly hair, and black skin [of African Americans & African descendants as a whole] were the characteristics of lepers.” He also said that black people have a greater propensity to have “insensitive nerves, uncommon strength, and venereal diseases.”[4] As an esteemed medical doctor, Rush’s words were very influential, both throughout society at large and within scientific communities. Furthermore, his belief that blacks needed to be civilized and morally restored through righteous living, went a long way in justifying paternalistic relations between Whites and Blacks. The clearest manifestations of this have been the oppressive systems of slavery and Jim Crow.

While Rush was one of the first U.S. scientists to offer “scientific” justifications for what was seen as the inferiority of African Americans, he was far from the last. A plethora of other physicians were involved in similar racial studies that enabled and emboldened the white power structure; a few of these physicians included noted scientists like Dr. John H. Van Evrie, Dr. Samuel Cartwright, Dr. Edward Jarvis, and Dr. Louis Agassiz. Furthermore, In 1853 Van Evrie wrote that his research revealed that black people were diseased, unnatural, and possessed impeded locomotion, weakened vocal organs, coarse hands, hypersensitive skin, narrow longitudinal heads, narrow foreheads, and underdeveloped brains and nervous systems. Van Erie concluded that the combination of these traits constituted racial differences and proved inferiority.

Similarly, in 1851 Samuel Cartwright in his “Report on the Disease and Physical Peculiarities of the Negro Race” diagnosed blacks as having insignificant supplies of red blood cells, smaller brains, and excessive nerves, which lead to what he called the “debasement of minds in blacks.” Furthermore, Cartwright asserted that “the physical exercise provided by slavery would help increase the lung capacity and blood functions [of African Americans]. Cartwright also believed that “slaves, sometimes were afflicted with “drapetomania,” a disease [which he created and claimed mentally disabled them] making them want to run away. The prescription for “drapetomania‟ he argued, was care and kindness, [from whites, who were to supervise them through paternalism, but he also asserted that] the whip should not be spared should kindness fail.”[5] Overtly racist studies and theories such as these continued to be produced and published by physicians into the early 1920s. This was a primary incentive for Woodson’s creation of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History and The Journal of Negro History. The residue of these racist studies resides within our collective psyche. The only way to purge ourselves from them is through the renewal of our minds and the indwelling power of the Spirit. Then and only then, will we be able to fully unearth scientific racism’s toxic effects and ponder anew what the baptismal waters are intended to do– reconstitute our family, bind our identities, and root them in Christ.

[1] The Enlightenment is a term used to describe a phase in Western philosophy and cultural life centered upon the eighteenth century, where scientific reasoning was elevated and advocated as the primary source and basis of authority within society. This movement ultimately aspired to replace the church and religion with scientific reasoning as the rationalization of God’s laws in the natural order of things.

[2] William H. Watkins, The White Architects of Black Education: Ideology and Power in America, (New York: Teachers College Press, 2001), 25.

[3] Watkins, The White Architects of Black Education, 25.

[4] Ibid, 27.

[5] Ibid, 28